If Tartarus of Greek mythology was real, it’s safe to say Sisyphus, sentenced to eternal punishment, would still be down there, trying his damnedest to push a boulder up a hill. Funny; I hadn’t considered Sisyphus’ plight when I watched The Year Long Boulder, the first short film by writer / director Brielle LeBlanc and producer Seán M. Galway. Yet the king of Corinth is precisely the first thing LeBlanc mentions as creative inspiration for their work.

“It’s an ancient image, Sisyphus rolling the boulder up the hill,” LeBlanc begins. “He pushes against the immovable and remains in that battle for eternity.” But of course.

Divided into quarters (one for each season), The Year Long Boulder is, well, about boulders. Emotional ones, namely, like the kind weighing heavily on Billy’s mind:

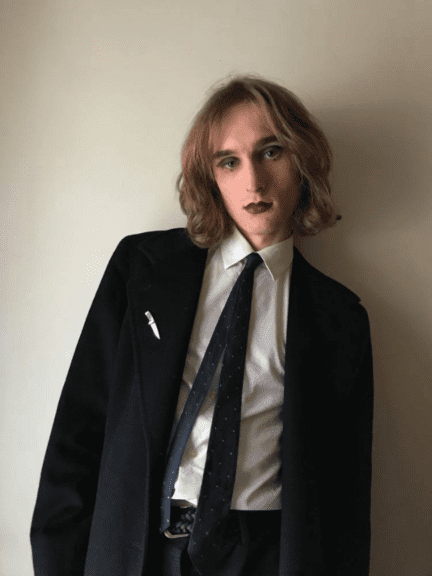

Billy (Em Grisdale), a poet who lives with their roommate Dylan (Marley O’Brien), isn’t sure if they’re about to kindle a romantic relationship with their new friend, or if the budding-but-exciting connection is strictly platonic. As fall turns to winter, as spring turns to summer — as questions turn to anxieties — Billy, with help from Dylan as emotional rock, finds the strength to speak to their true feelings, even if rejection is to be etched in stone.

The story of The Year Long Boulder, then, becomes not about the impossible act of attempting to move something unmovable, but rather about surrendering to the space the boulder takes up and working with it.

“I became interested in the image of a person and a boulder being emotionally intertwined,” LeBlanc says. “The story of The Year Long Boulder, then, becomes not about the impossible act of attempting to move something unmovable, but rather about surrendering to the space the boulder takes up and working with it.”

In Billy’s case, they work with their boulder by writing about it. Poems, specifically, workshopped with Dylan in their apartment. “There is a lightness that Dylan brings, which always acts to counter the heavy parts of Billy’s internal world,” says LeBlanc, much a poet of their own. These poems are a way for Billy to process, even refine, their inner thoughts.

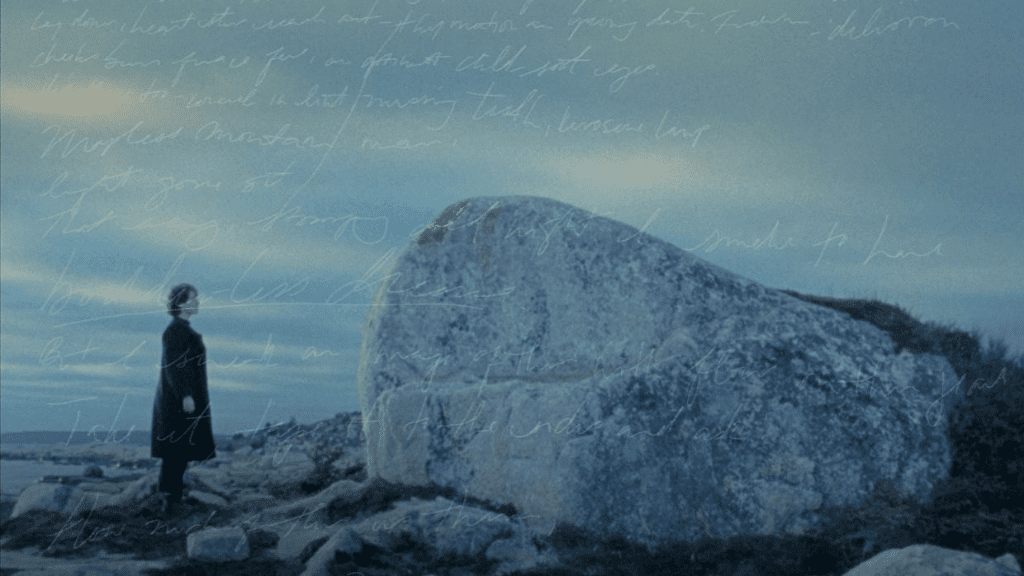

As audience members, we get to hear and watch Billy recite these poems, these inner thoughts, which, simultaneously, are overlaid as hand-written scrawls atop The Year Long Boulder’s use of film stock.

When the seasons change, Billy’s writing — read aloud in their apartment — transports them, and us, to a giant boulder (physical, this time) sitting motionless by the sea. Photographed on a mix of 16mm and Super 8, it’s this rock that Billy climbs and scrambles no matter the weather, and it’s special every time.

“It was a logistical challenge — everyone kept saying so — but going with analog over digital created a tunnel for my vision to follow,” LeBlanc explains. “The film is divided into two worlds: the material private home and Billy’s internal poetic coastline. I knew they had to be visually contrasted. I wanted a really clear image for the static wide shots in the dialogue sequences between Billy and Dylan, and 16mm was an easy choice,” they add. “With the boulder, Super 8 gave us the flexibility we needed for run-and-gun montages.”

But how does one locate a giant boulder for the second world? The titan of the title — so essential to the film — was hard to find. “It took three location scouts and many nights on Google Maps Satellite to find our film star,” LeBlanc says. “On the drive back from the second scout, listening to a Patsy Cline tape, exhausted in the back seat, I saw the boulder on the side of the highway. Wordlessly, I marked the coordinates and returned to them at a later date. When we returned and crested the hill before the boulder for the first time, I knew with certainty that it would be the visual stamp for the film.”

While hefty in size and thematic import, the boulder is still only half of LeBlanc’s equation. Billy’s story, a full year long, encompasses each season, the changes of which are seen subtly, such as updates to the apartment and the clothes on their coat hooks.

“Looking at seasons more abstractly, there are timeless habits revolving around them that affect our actions,” says LeBlanc. “Winter is often a time for turning inward, both physically and mentally. Contrastly, summer can be impulsive and active. The fall — excited, fresh, bountiful. Spring — an awakening, a hopeful stretch.”

It’s not a spoiler to mention Billy’s story ends with the arrival of summer (“impulsive and active” is a great way to describe it), because, perhaps, the warm weather is the ideal time to make a move. “It’s interesting to think about the effect of the seasons on Billy: In reality, we never see them outside of their domestic sphere, which is crucial. And I think in a way, that the house exists semi-separated from the exterior world. It’s almost as though the house has its own seasons.”

It’s true. As the calendar advances, every instance we see of Billy and Dylan’s living room looks different than the last, each meticulously designed: A rotating visual array of art, knickknacks, instruments… everything. There’s even a chess board set to the classic Giuoco Piano (“quiet game”) opening, which, LeBlanc reveals, intentionally puns on the film’s plot.

“In Billy’s reality, the division of a year into seasons may seem to indicate definitive change, but that shift is so gentle, you only really notice it in hindsight. And maybe that’s it — maybe the changes of seasons / changes of self are so much less definable or visible than we think.”

“The movement of change, though slow, still results in a transformation. I wonder what Billy would say if someone asked them how their year was,” LeBlanc asks. “Are we really so conscious of our changes? Or do we just experience them in a benevolent sweeping motion, being softly impacted by those innate seasonal tendencies?”

The Year Long Boulder plays as one of the nine shorts selected for “Seasons, Change,” the latest iteration of Telefilm Canada’s Not Short on Talent at Clermont-Ferrand 2023.

In creating Boulder, LeBlanc and Galway have launched Enodia Films, their production company, which has two short films on its development slate (including Burnt Toast, which captures two neighbours on their front steps talking about the gentrification of their street, with LeBlanc directing from a script they wrote). Galway, additionally, has written a project to direct, one entitled Metaphysical Import-Export, an experimental piece about transmisogyny in history.

JAKE HOWELL

Jake Howell is a Toronto-based writer and freelance film programmer.